Building a DNS C2 Framework from scratch

C2 (Command and Control) is a Server-Client communication method, mostly referred to as malicious communication between a trojan, malware or any other malicious program to the “mothership”. The C2 server usually has 100s if not thousands of clients connected to it, and each client (compromised device) can act differently and behave in a certain way.

C2 is a generic term. The malware samples I’ve come across have used various methods to establish the connection to the command and control servers. Some of the interesting ones include: - Reading metadata inside a Tweet picture to get the next action - Analyse comments on Britney’s photo on Instagram and decrypt the message - Login to Gmail/Outlook and use the email’s builtin features - Pure HTTP connection to an IP/hostname

some of the more “advanced” threat actors use DNS as a stealthy method of getting commands and running them on the victim’s box. due to DNS protocol limitations, the data exfiltration and lateral movements usually don’t happen in this layer. Sometimes that comes as a simple upload to dropbox or an S3 bucket rather than purely using DNS to move around tons of data.

but C2 doesn’t always a “bad guy” term. In any service that has a minion-master relationship, the master could be considered a C2 server. A good example of that is some deception tools such as the Canaries, which have always been interesting to me.

The canaries are small Raspberry Pi-like boxes that you plug in and hook to the network, and as long as it has DNS connectivity, it’ll try to work with a central server via DNS and grab commands, configure itself and send alerts if anything happens to the box. A very good example of DNS C2 being used for good :)

dnspot

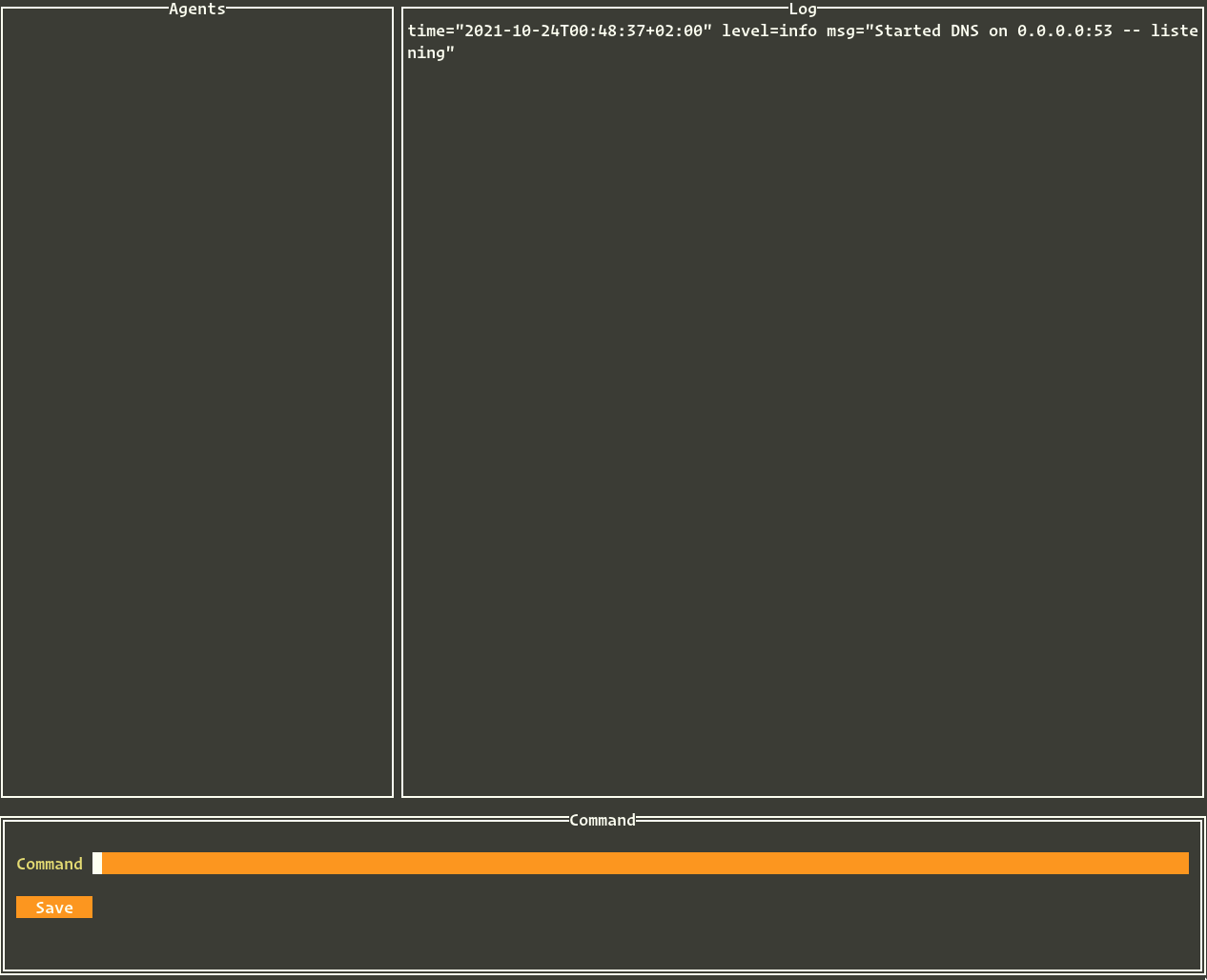

This prompted me to start thinking about how can I create my own DNS C2 framework, and how do I make it extensible enough that it doesn’t rely on a honeypot product to be useful. I wanted to make it both standalone and as a library, and make it robust enough to endure network disruption, bad latency, and wrong message order. That’s how dnspot was born.

dnspot creates a simple transport layer working on top of DNS, and builds a mandatory symmetric encryption layer based on ECC to encrypt the data in transit. It also uses a custom implementation of base36 as an encoding method for the generated E2EE packets, just to make sure all DNS servers in the world would be happy with it, since base36’s alphabet falls under allowed chars in a DNS record.

dnspot uses a standard implementation of NIST’s P-256 elliptic curve + SHA-256 to transfer data securely over an A query. The responses from the C2 to each agent are sent via a CNAME response with the same algorithm, so a lot of underlying C2 and Cryptography functions are shared between the agent and the server. A custom transport protocol has been implemented to ensure the delivery of payloads in various sizes. Before encryption, each packet looks like this:

|

|

If there’s a large command or response, this message structure allows it to be split into multiple queries, while maintaining the cryptographic integrity of each packet, since the signature and encryption will happen on top of MessagePacket, meaning all the MessagePacket will be encrypted and signed, not just the payload. Right now, PAYLOAD_SIZE is 80 bytes, which gives the user the ability to have up to ~30 character DNS suffix and the system still works.

Technically, DNS has a lot of question and response methods, and some of them might even give me a higher bitrate than the one I use, which is a simple A record. The A record has a 255 character max limit, can not have case-sensitive characters and will need each “subdomain” to have 64 character max.

Since I needed to have the same structure from the server-side, I opted to send the responses back as CNAME records, which are basically the same as A records but can be inside the response packet.

How does it work

The connection always starts with a “health check” packet initiating from the agent to the server, with an A query with some details around the time of day, and the request will be signed by the private key of the agent, which automatically authenticates any incoming packet. This feature is loosely inspired by Wireguard. leaving the minimum footprint on the packet payload, and focus on authentication and authorization with ECC

A sample initial A query might look something like this:

jtixj4qjifvduc9s5pjboo4pkw73b0a9ez26rle922h058rsytvl3vs13a16ieb.kr4sxkatiqskamq6ddho80lcfuu4nmqzji5poaaj3yp5q3hu7pzg1gbu10bvf1r.3b93owkoihna837jw6xfl83idu3e0vkriakofu62jbaqfwjp5igzrarmmxchzxw.pzv5jnxihtttei5zr9chg7vbl.c2.cdo.wtf

as you can see, the base36 stream has been broken up into pieces by a . to make sure that the string technically passes DNS specifications. the entire payload struct will be encrypted and signed by the agent before being put to the wire. It’s also trivial to make this work over DoH or DoT and add an extra layer of protection to the payload, but in essence, we don’t need to worry about the carrier network for the packet.

for each incoming packet, the server registers the agent initiating the request. Optionally the server can have a whitelist of allowed agent public keys to make the C2 framework somewhat private. although re-using the private key of a different agent is not prohibited since there’s no good way to track the source IP of each agent.

Once the agent is registered in the server, the server is allowed to put an arbitrary command on the client’s “queue”, which means the next health-check packet won’t be responded to by a simple “ack”. Rather, the server will issue a state change command as a reply to the agent. This will kick off a rapid back and forth of A queries and CNAMEs between the agent and the server to communicate what command needs to be run on the agent. The multi-packet nature of the payload allows for massive commands and massive responses from both sides. In theory, 1GB of data can be transferred this way between the two parties.

since there’s the ability to have big arguments and/or responses in the code, the command and control server can either send additional payload and/or executables to the target machine, or ask the agent to cat a file back, which essentially translates to data exfil. The server comes with an optional log file to make sure if the server exited, the data being transferred are still logged somewhere.

This simple yet effective approach, allows us to basically have an overlay network on top of DNS, relying only on PKI for the identification of each agent. IP address, MAC address, etc do not matter to this method.

Relationship with honeypots

So far, the framework itself was put under the microscope. But as far as a product goes, this offers little to no value as a deception tool. This is where the next phase of the project will come into play. Ideally, the dnspot project will not have a dependency on the UI as it has right now. I’d like to turn dnspot into a library with pre-defined APIs so any other program can use it as a method of communication without worrying about configuration.

In some environments, it’s unfeasible to have network connectivity back to any central location via HTTP/HTTPS or even SSH. The environment is too restricted to allow such a thing. And I would argue that those networks are the perfect place for a deception tool to shine. This is where the marriage between dnspot and any other honeypot framework will come to play. If dnspot turns into a networking framework in the future, it can be easily used as a great tool to implement honeytraps in

highly segregated networks. DNS is usually allowed anywhere and even if it’s not, DNS to one domain is usually a very small attack surface.

Final Thoughts

I did NOT design this to be a bad guy tool. Not supporting Windows platform is a big part of that. also, detection of the A record, as well as the CNAME responses, is easy enough for the defenders. As a defender myself, I learned quite a few things by writing this project and trying it in the wild:

- you can use dnspot as a quick DNS security benchmark tool to see if you can breach out of your network using DNS

- you can use dnspot to build secure connectivity between highly sensitive networks and your infra using DNS as a decentralized database and routing system

- you can use dnspot in conjunction with honeytrap to build good deception tools and elevate your security posture

- learning ECC is good :)

- learning DNS is good :)

I hope you enjoyed this as much as I did. This might be one of my favorite projects!