Basic guidelines that would've prevented SUNBURST

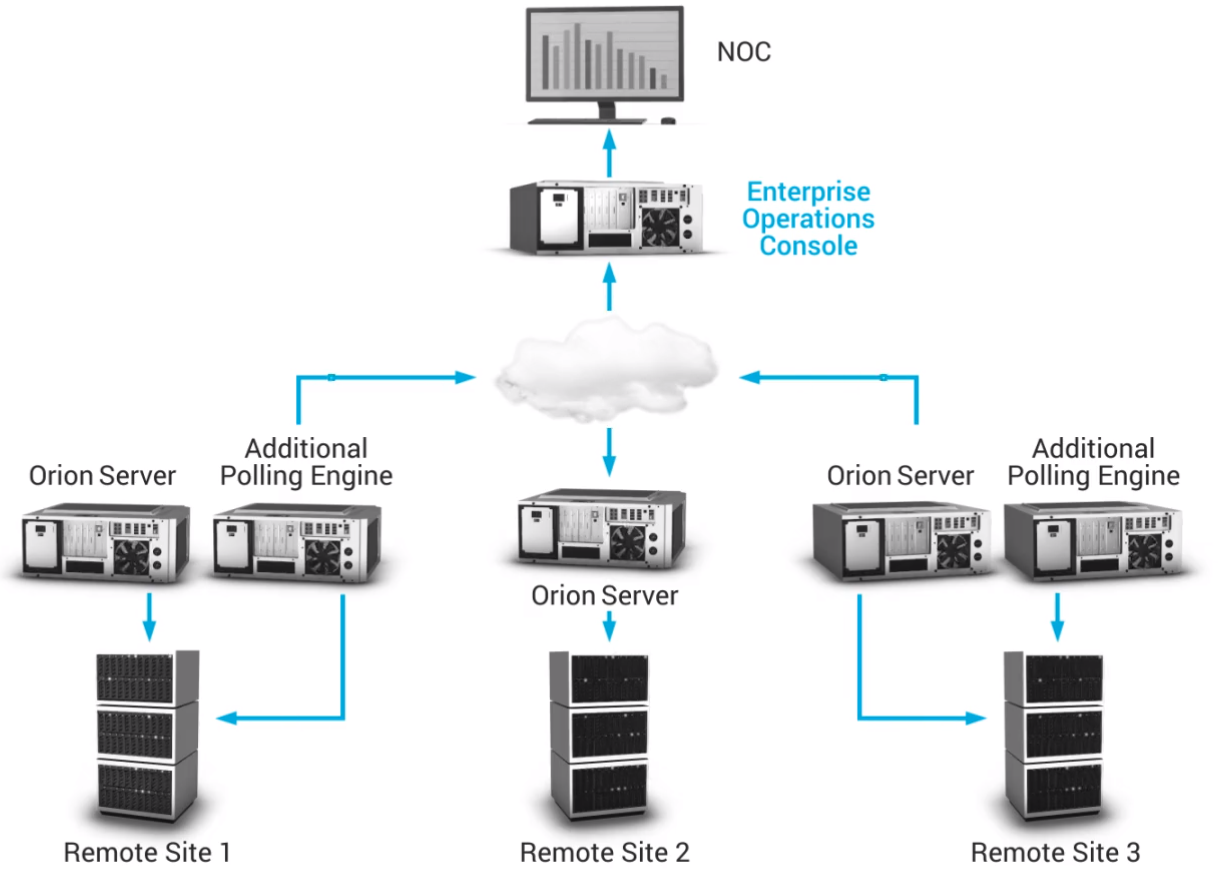

First off, let’s have a brief overview of what SolarWinds Orion is and what’s it good for. Orion’s main purpose is to give a single pane of glass to look at your IT infrastructure. Various technologies can pump their metrics into Orion Database using Orion poller as a proxy. Orion Pollers will sit in your network, consume the metrics they need, and push it to the database engine. From the design perspective, it’s a robust, effective, and scalable way of having the data always ready. Oh btw, SolarWinds has nearly 18,000 customers worldwide.

If you’ve implemented Splunk heavy forwarders, Syslog Servers, Elastic Beats, OSQuery agents, and hundreds of other products, this looks familiar. In their website, SolarWinds has pointed out the security requirements of agents connections to Orion Server on ports 22/TCP, 17778/TCP, and 17790/TCP.

So far so good? let’s see where the problem is (hint: as always, it’s a human error)

The case of a Trojan Horse

In a somewhat unknown incident, believed to be before March 2019, someone gained access to the SolarWinds update server. According to Reuters, Security researcher Vinoth Kumar alerted SolarWinds that anyone could access SolarWinds’ update server by using the password “solarwinds123”. So the assumption is, getting access to the update servers was not difficult in early 2019 or before. Unlucky for the rest of the world, whoever gained access to that update server, didn’t use it to install xmrig and mine Monero or join it to a Botnet. Instead, they tried to learn how the CI/CD pipeline works inside SolarWinds. We don’t know much detail on that but what we do know is, by March 2019, an update for Orion software had an extra “patch” in it and it went completely unnoticed by SolarWinds, got signed, and pushed to the mass. I won’t copy and paste all the technical details of the DLLs and hashes etc here, since Microsoft nailed it with their series of blogposts on the subject.

Long story short, SolarWinds.Orion.Core.BusinessLayer.dll is now a classic trojan horse. It has a dormant period and after that, it tries to call home (avsvmcloud[.]com) and get instruction, jobs, and so on.

So, we have 18k customers of SolarWinds, most of which would’ve updated their product to an infected version, hence having a backdoor in them. That backdoor is self-activating to that one domain and that one domain only. It will ping that domain to get further instructions and possible next “stable” C2 connection domain for further activity.

What I’m trying to wrap my head around is this: why does a close-design ecosystem like SolarWinds Orion is implemented in a way that the Orion agent/software has access to that particular domain?

Server vs Endpoint Internet Access

It’s fairly well-understood that your company laptop’s internet gateway shouldn’t be the same as your fleet of servers in your Data Centre. I’m hoping that we’re all on the same page that servers don’t need to check their social media account secretly at 10am, but we do. For your internet-facing server fleet, your load-balancers and Firewalls will sit in front of your servers, preventing any outbound connection and only allowing “sane” traffic to come through, so even if you’re web server is literally serving traffic to the entire world, it doesn’t need the ability to have direct internet access to any IP at all.

In fact, I would go as far as saying no well-designed server in the world needs direct internet access to the whole IPv4 range. If you have an EC2 instance right now and you’re thinking that instance has internet access and I’m fine with that, take a look at this architecture design by Amazon.

According to Microsoft’s technical blog:

In its first step, the backdoor initiates a connection to a predefined C2 server to report some basic information about the compromised system and receive the first commands.

Based on what we know so far, it’s safe to assume that in every single victim company, there has been at least one Orion installer with full internet access. That includes Cisco, Intel, and a lot of US Government agencies. I wouldn’t be surprised if the successful C2 communications came from a cloud instance. By default, a lot of compute nodes within any Cloud environment have unlimited internet access.

so, the next logical question is: where does SolarWinds.Orion.Core.BusinessLayer.dll usually sit? Is it found on endpoints or servers? The answer is simple: it almost exclusively sits in servers.

What’s Next

I hope that by now my point is very clear. From my point of view, only one thing made this attack stand out among others. The fact that SolarWinds got pwned by an attacker and the attacker was clever enough to use that entry point to inject code. The rest is essentially the same crap that we’ve been dealing with for years. That’s why we created DMZs and ACLs on our Routers and Switches and Firewalls. We acknowledged a long ago that trusting in “one thing” is wrong. We’ve seen this before and we’ll definitely see it again soon. The answer to the question “what’s next?” is pretty boring and predictable, but we’ll go through a couple of them relevant to this particular incident.

-

Servers are not endpoints. They should have an IP allowlist rather than an IP blocklist. They should NOT have access to the internet except for a few allowed CIDRs and domains. Keep in mind that if you’re not breaking SSL in your proxy, make sure to whitelist correctly, since domain whitelisting is often unreliable. for example, if the attacker takes over a server that’s allowed to access Google.com but with any IP, they can just add their C2 server to the “hosts” file of the victim as google.com and bypass your restrictions if you’re not careful. Also, if you’re using a proxy, having a domain allowlist based on source IP + authentication is the best way forward. Unfortunately, you can’t rely on authentication only since if the attacker has a foothold inside your network, they can just sniff another set of creds, possibly from an endpoint, and initiate their connectivity with an endpoint profile but from a server IP.

-

Host your own DNS: if you’re allowing your endpoints to talk to any DNS servers outside your organization, think again. DNS Tunneling is real and it’s a very tough nut to crack when it comes to defense. This Video provides a good overview of attack and defense tactics for DNS.

-

Avoid flat networks as much as you can: it’s hard to count your FW denies if the packets don’t reach the FW to be denied. We can’t trust our neighbors in the network to not

nmapus 24/7. East-west protection and detection is a good step towards a Zero Trust network implementation. Also, if you’re in a comfort zone of RFC1918 for your server, and you think nothing bad comes from RFC1918 IPs, you’re not thinking of your lateral movement risks. -

Anomaly Detection vs Traditional SIEM rules: if your server is contacting a new IP or a new domain that you haven’t seen in your organization before, that’s an alarm. This is a DFIR layer on top of what we already discussed in terms of access control management and IP allow listing. to have the assurance that your FW is doing its job properly, have a rule in place to see if a particular server is connecting to a brand new IP out of the blue. That’s a red flag and that’s usually how you get ransomware as well. Splunk has a great article for building new domain rules.

-

Patch, patch, patch: “but if I didn’t patch, I wouldn’t have a backdoor-ed version,” you say. Well, in this particular incident, yes. but even so, I would rather be attacked (and defend against, by doing my defense in depth) by an attacker that did their homework than a script kitty pulling code from Github and pwning my shit, which is what would happen if you don’t patch. Does that make sense?

What year is it, 2010?

I know right? What I just talked about is very well defined and agreed upon within cybersecurity domains, and none of them are radical. Yet, looks like even major companies fall into not having 100% coverage of these simple policies.

Big takeaway is this: servers and endpoints falling off from your Golden standards is a very common theme across organizations, big or small. Best to have a plan to verify and provide assurance of your standards and keep track of those who fall behind. IT is a very fast-paced environment and it’s almost impossible to do this manually. Each organization needs to have its own automated way of keeping track of security sanity checks. Hate to be “that” person, but defense is not all cool forensics and finding tracks of malicious, ephemeral code in RAM. It’s keeping the weakest link as secure as you need it to be. If you’re seeing a company in the news for ransomware or a massive data breach, I’m sure their CISO is thinking “but we’re 90+% secure”, and she/he’s right. Odds are their “strong” sites are ok but some test instance somewhere had a misconfig and fell out of patching cycle and it happens to have some hardcoded creds in a text file, leading to a massive breach.

Keep up with 2021 but bring your y2k stuff forward too, Happy hunting and Merry Christmas.